I was recently presented with the problem to automate the deployment of a nuget package to a server. Now before you guys say I know that Octopus Deploy is the best way to go and I completely agree. At the moment at the organisation I’m at using a product like Octopus has to go through an “approval” process. Faced between the choice of having to carrying on deploying using file explorer (which is what the guys currently did here) and automating it, I voted for the latter option.

Now Team City is not really geared towards doing deployments. After all it’s designed to be a build server and that’s what it does extremely well. However we can make it work.

The first thing you need to do is package up your built web site into a nuget package and deploy it to a nuget server (either a local one or the public one). For those that dont know a nuget package is literally a zip file, you can even rename it .zip and it will extract. The reason for using a nuget package is that it gives you a nice way to place it onto a server, version it and in the future plug in Octopus Deploy.

So onto the script:

param([string]$computerName, [string]$destinationDir, [string]$packName, [string]$packVersion, [string]$executeLocally)

Write-Host "computer name: $computerName"

Write-Host "destination dir: $destinationDir"

Write-Host "package name: $packName"

Write-Host "package version: $packVersion"

Write-Host "execute locally: $executeLocally"

$deployScript = {

param($dest, $packageName, $version)

$basePath = "d:\packages\"

$packageNameAndVersion = "$packageName.$version"

$extractDir = $basePath + $packageNameAndVersion

Write-Host "deploying to: $dest"

Write-Host "extracting to: $extractDir"

Write-Host "package: $packageName"

Write-Host "version: $version"

$zipDownload = $packageNameAndVersion + ".zip"

$packageUrl = "http://nuget.org/api/v2/package/$packageName/$version"

if (-Not (Test-Path $extractDir))

{

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path $extractDir

}else{

Get-ChildItem -Path ($extractDir + "\*") -Recurse | Remove-Item -Recurse -Force -Confirm:$false

}

$Path = $basePath + $zipDownload

Write-Host "Downloading package..."

$WebClient = New-Object System.Net.WebClient

$WebClient.DownloadFile($packageUrl, $path )

Write-Host "Extracting package..."

$shell = new-object -com shell.application

$zip = $shell.NameSpace($path)

foreach($item in $zip.items())

{

$shell.Namespace($extractDir).Copyhere($item)

}

Write-Host "Cleaning destination..."

Get-ChildItem -Path $dest -Recurse | Remove-Item -Recurse -Force -Confirm:$false

Write-Host "Deploying..."

Copy-Item ($extractDir + "\*") $dest -Recurse

Write-Host "Removing downloaded package from $path"

Remove-Item $path -Recurse -Force -Confirm:$false

Write-Host "Removing extracted package from $extractDir"

Remove-Item $extractDir -Recurse -Force -Confirm:$false

Remove-Item ("$extractDir\") -Recurse -Force -Confirm:$false

Write-Host "Done."

}

$output = Invoke-Command -ScriptBlock $deployScript -ArgumentList $destinationDir, $packName, $packVersion

Now when you configure your team city build you need to pass in the following 3 parameters: $destinationDir, $packName and $packVersion. The destination dir is the directory you wish to deploy to e.g. \\192.168.1.1\WebSites\MyWebSite. The package name is the package id of the nuget package and the packVersion is the version number of the nuget package. That’s it! Simply huh?

You will need to make sure that the Team City user account has write access to the folder you are deploying to.

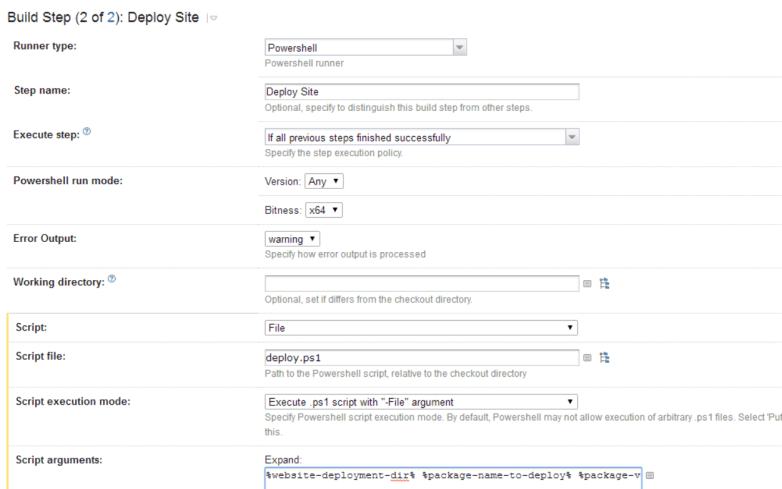

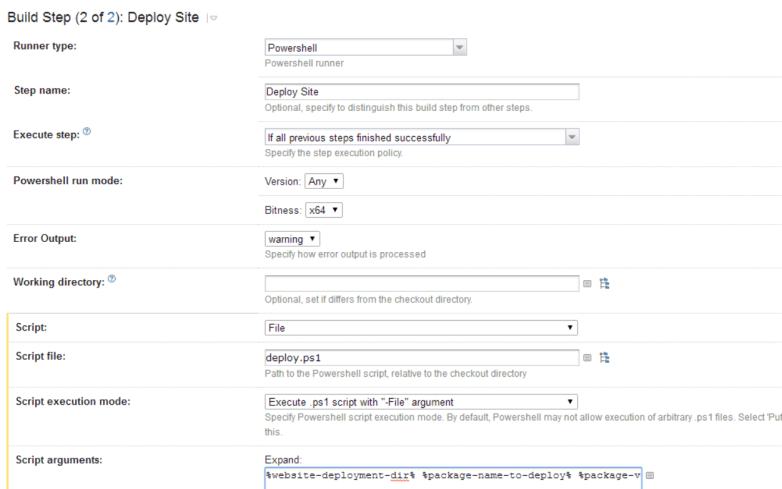

In the screenshot above you can see how to setup the powershell script to run. You can either check it into your source control system and then enter the path to the file in the script file dialog above or alternatively you can copy and paste the source directly into Team City. I would recommend having the powershell script in source control as then if you have multiple deploy builds changing the script will mean every build will get the new powershell script.

In the script arguments dialog you need to pass in the parameters to the script described above. You can either hard code these (not recommended) or you can use Team City parameters and then present the user with a dialog when they go to run the build. To do this I use the following parameters:

%website-deployment-dir% %package-name-to-deploy% %package-version-to-deploy%

After you have saved this, Team City will prompt you to setup these parameters. Go to the parameters section of your build configuration. Click on one of the parameters. Click spec, then in the dialog that appears next to display select “prompt”. You can enter a default value if you wish or even give the user a dropdown select with for example every website they can deploy. By using the prompt option when the user clicks to run the build they will be presented with a dialog that will force them to enter these parameters.

So there you have it, a quick and simple build that can deploy any nuget package to any server. Simples.

As always if anyone has any questions or wants to go through anything feel free to contact me. Happy deployments!