As mentioned in my last post I’ve recently got into solving HackerRank problems in F#. I’m trying to use F# with a functional programming style not writing in an imperative style as I would in C# and use the F# syntax (which is possible).

I want to go through how I solved the Grid Search Problem so if you don’t want to know a solution look away now!

The problem is that you are given two grids of numbers and you have to write “YES” if the second grid is contained anywhere in the first grid and “NO” if it isn’t.

I’m quite new to functional programming but the way I approached this was to break the problem up into smaller functions and then the answer would be a composition of those smaller functions.

If you clone my HackerRankInFSharp repository from github it contains all of the code that you can follow along to. To view the code for this problem open the file GridSearch.fs in the HackerRank project.

At the bottom of the GridSearch.fs file you will see a solution function defined. This function runs the test case from the input file and is where you should start reading the file from.

When you run your code on hackerrank your program needs to interact with the console. To save typing the inputs in each time I wanted to test my program I copied the test cases into a text file and then simply mapped a read function to reading a line from a file like so:

let reader = new StreamReader("TextFile1.txt")

let read = reader.ReadLine

This is one of the neat things about F#. As it’s a functional language and functions are first class citizens you can assign them into variables and then just pass them around. By writing my code in this way I could simply copy all of my solution into HackerRank when it is complete and just change the read function to map to console readline (let read = Console.ReadLine) and leave the rest of my code the same.

The next three functions that I wrote are to help read the input data:

let t = read() |> Convert.ToInt32

let num = fun() -> read().Split(' ')

|> Seq.head

|> Convert.ToInt32

let fetch = fun() -> [for _ in 1..num() do yield read()]

The first two simply read the values for t (the amount of test cases) and num I use to be the amount of rows in the grid. The input data also gives you the length of each row but as the rows are separated by new lines you don’t need this. The last function fetch returns a sequence of strings of length num (the amount of rows in the grid). The function fetch will be used to read a grid into a variable and is generic so can be used both for the reference and search grids. The terminology I’m going to use is reference grid to refer to the bigger grid and search grid will be what we are looking for inside the reference grid.

Now I’ve got the input my idea was to write a function get all indexes of a smaller string in a bigger string. The reason for this is that I thought to search for the search grid inside the reference grid we would first start with just the first line of the search grid. We want to look at each line of the reference grid and know if the first line of the search grid is contained within it. If it is we want to a list of the indexes of where it is.

let allIndexOf (str:string) (c:string) =

let rec inner (s:string) l offset =

match (s.IndexOf(c), (s.IndexOf(c)+1) = s.Length) with

| (-1, _) -> l

| (x, true) -> (x+offset)::l

| (x, false) -> inner(s.Substring(x+1)) ((x+offset)::l) (x+1)

inner str [] 0

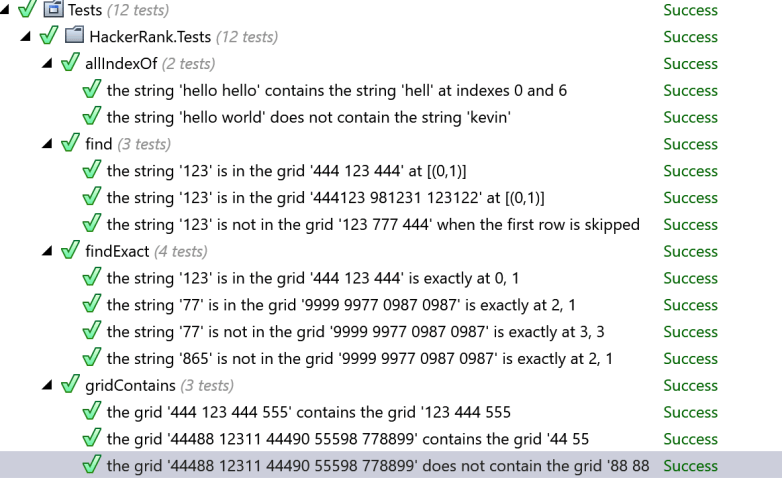

In my last post I talked about the awesome help I got off the community with this function. This function works recursively which is one of the mantras of functional programming. allIndexOf takes 2 strings. The first string is the reference string (str) and the second string is the one you are looking for (c). The first line of the function declares a recursive function that takes a string (s) a list of int (l) and an int (offset). There are a few interesting points on this line. Firstly the keyword “rec” is not optional, it means it is a recursive function. The next interesting part is that the parameters l and offset do not have any type annotations. This is one of the things that makes F# very clean. The reason for this is that the compiler can figure out the types of the functions nearly all of the time for you so the type annotations are completely optional. This removes a lot of the excess clutter. The next line (match) is another very cool feature of F# The pattern matching. What it is saying is create a tuple that as the values (s.IndexOf(c), (s.IndexOf(c) +1 = s.Length)) which is of type (int, bool). Once that tuple is created it is then matched on one of the next three lines. If s.IndexOf(c) returns -1 then it doesn’t matter what the second part of the tuple is as we match with the wildcard _. In that case we return l the list that was passed in. If the s.IndexOf(c) evaluates to anything other than -1 then we match the 2nd line if the bool part is true. If the bool part is false then we match the last line. The last line of the function then calls the recursive function with the string you have passed in, an empty list and an offset of 0.

To see how this function works lets look at a simple example if we pass in “hello hell” and “hell” we would expect the indexes returned to be 0, 6. When we call the function inner with “hello hell” [] 0. The match clause will then produce the tuple (0, false) which will match to the third line. This will then call inner again with “ello hell” [0] 1. This time the match clause will evaluate to (2, false) which will then call inner with “ell” [0, 6] 6. This time the match clause will return the tuple (-1, false) so it will match with the first line of the match clause and return the list [0, 6] which is the correct answer.

The way you can combine functions together to perform the tasks you need will become clear as I go through the rest of the solution. The next function uses the allIndexOf function to return the co-ordinates of every occurrence of a string in a list of strings (aka a grid).

let find g str start = g |> Seq.skip start

|> Seq.mapi (fun i x -> (allIndexOf x str) |> Seq.map (fun u -> (u, i+start)))

|> Seq.collect (fun x -> x)

You can read the |> operator as pipes data from left to right. What we are doing here is for each row in the grid skipping as many rows as are passed in via the start parameter (note this is an optimisation as further on we can reuse this function to search the remainder of the grid). We then pipe the result from that into a map function that returns a tuple where the first element is the index of the string (x co-ordinate) and the indexer is the y co-ordinate of the string. The y co-ordinate of the string is known as we are looping through each string in the grid using the mapi function. The mapi function gives you each element (x) and the index of the element (i). The index of the element will be the y co-ordinate as that corresponds to the row in the grid. We then have to use the Seq.collect function to unwind a double sequence. This is the equivalent to a select many.

let findExact g str x y = find g str y

|> Seq.exists(fun (a, b) -> x = a && y = b)

The findExact function then extends the find function to return a bool if and only if that string is found in the grid at the co-ordinates specified. The reason for this function is my idea to solve the problem is to call the find function for the first row of the search in the reference grid giving you all of the co-ordinates of where that appears. Then all you need to do to tell if the whole search grid is there is loop through subsequent rows and add one on to the y co-ordinate each time. For example if we called find and we got back (2, 3) and (5, 6) and the search grid was 3 strings deep. Then to tell if the search grid is in the reference grid we would simply need to know if the second string was at (2, 4) and the third at (2, 5) or if the second string was at (5, 7) and the third at (5, 8). In either case the answer is yes, if any of those return false the answer is no.

let gridContains g (s: string list) =

let matches = find g s.[0] 0

let numStrs = s |> Seq.skip 1

|> Seq.mapi(fun i line -> (i, line))

matches |> Seq.map(fun (a, b) -> numStrs |> Seq.map(fun (i, line) -> findExact g line a (b+i+1)))

|> Seq.exists(fun b -> b |> Seq.forall(fun x -> x))

The function above does exactly that. The first row assigns all of the co-ordinates of the first row of the search grid that are found in the reference grid into the variable matches. The next line essentially numbers each string in the search grid but not the first row making it easier to write the last part of the function. The last part of that function then pipes matches into a function that for each co-ordinate in matches adds on i (the current loop value) to the y value and 1 (due to 0 starting value) and returns a bool as to whether that string is contained in that position. That will then return a sequence of sequence of bool. The last part is then to see if any of those sequences of bool contain a set of all true. It even reads how I’ve just described it “does a sequence exist where there is a sequence for all of which are true”.

To run the solution clone theHackerRank repo on github. Then in the program.fs file uncomment the line //GridSearch.solution.

I’m still new to functional programming so if there is anything you would improve or do different please feel free to leave a comment below.